By David Abel | Globe Staff | 11/23/2003

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 11/23/2003

FROM HIS DEATHBED, WHERE HE ARRIVED on his 100th birthday, Arnold Stephens wouldn't stop cracking jokes, no matter how many of his friends bawled or prayed he would sit up, free of all the tubes and pumps, and shuffle off, like he was hitching another ride to Burger King.

A World War II veteran who reached my age during the Great Depression, it seemed he embodied everything I wasn't, everything I aspired to be.

An unrelenting optimist, Arnold could make the most morose characters laugh, even an oncologist explaining the extent of his cancer. At 30, when he sold gallons of soap during the Depression, he liked to say, "I squeezed the nickel so hard I could make the Indian ride the buffalo on the other side of the coin."

Though he owned an apartment in one of the wealthiest parts of town, a two-bedroom condo that could have fetched more than a half-million bucks and had the word "Royal" embroidered on the brownstone's burgundy awning, he remained a self-described "cheapy" to the end -- eating at "church dinners" after his wife died 20 years before, sticking out his thumb for a ride to Copley Square, or savoring the tapioca pudding nurses served him in his final days.

I met Arnold two years before at one of his church dinners, a soup kitchen a few blocks from his apartment. As I waited for someone else, I couldn't help noticing as Arnold, stooped yet seemingly hale, regaled a table full of grumpy old men.

I walked over to the short man, who sat at the head of a table in a rumpled brown suit, and listened as he told one of his self-deprecating jokes: "I went into the store to buy a piano the other day and asked if I could buy it on the installment plan," he was saying. "They wouldn't sell it to me ... Go figure.''

Then I got a glimpse of how he could eat. The scrawny guy had the appetite of a sumo wrestler. As I watched him move from pork burger to coconut pie, devouring each, I asked if he had enough at home. "I have a microwave, but if I don't have anything to eat, I just starve," he said, pausing for a few long seconds, his saggy jaw unable to conceal the coming smile. "Yeah right."

To be sure, Arnold lived off a meager income - he relied on federal aid just to pay the taxes on his condo - but his pension provided more than enough to eat. I wrote about him in a front-page story about land-rich, cash-poor seniors who scrimped by because either they wouldn't move or refused to hock their homes for so-called reverse mortgages. The soup kitchen's buffet-style free food surely had its appeal, but the real reason he ate there and at other churches was "to meet the fellas," as he liked to say, or "shoot the baloney."

It was hard not to like Arnold, who never had children and whose only relatives were three nephews, just one of whom he saw regularly. His exuberance quickly breached the walls I had come to naturally build as a reporter, and I soon found myself dropping by his dust-covered apartment, not to check up on him, but to chat. It didn't take long before we became pals.

One thing I never could understand, though, was what possessed a man in his late 90s to hitchhike.

Arnold, of course, had a simple explanation. "A man has to get around," he would say, his squeaky voice rising and falling with every syllable.  Like many seniors, especially one who spent his life traveling through Europe and Asia, Arnold thrived on going places, which made it particularly hard to give up driving. In fact, he remained behind the wheel until only a few years before, when he was 95. But he lived in a big city, I noted, wasn't it risky? How did he know he wouldn't find himself in a dangerous situation? He didn't think much about it, because it came down more to dollars than sense: He refused to waste money on a cab. So, for pragmatic reasons, he took to hobbling out to the curb, sticking out his thumb, and waiting patiently. "People are nice," he said with another disarming smile. "They're all my friends.''

Like many seniors, especially one who spent his life traveling through Europe and Asia, Arnold thrived on going places, which made it particularly hard to give up driving. In fact, he remained behind the wheel until only a few years before, when he was 95. But he lived in a big city, I noted, wasn't it risky? How did he know he wouldn't find himself in a dangerous situation? He didn't think much about it, because it came down more to dollars than sense: He refused to waste money on a cab. So, for pragmatic reasons, he took to hobbling out to the curb, sticking out his thumb, and waiting patiently. "People are nice," he said with another disarming smile. "They're all my friends.''

I learned a lot over the two years I palled around with Arnold. There would be lessons about life, and death.

He presented a model for a man who could live contentedly with few material possessions. The passage of time, whether it slowed late at night or sped up when he looked at a calendar, never tormented him. He could be as comfortable with silence as with a deep conversation. He knew how to laugh and how to tell a joke; but he also knew how to listen and how to comfort. And unlike many former soldiers of his generation, he never hid his affection, often telling me of all the friends and family I brought to meet him, "Tell them I love 'em."

Nothing - other than cute girls and good food, of course - gave him more pleasure than giving presents. More than anything else, he liked to record old movies and send visitors home with tapes. Whenever I asked if I could bring him something, all he wanted were blank videotapes, which he always insisted on paying for. On each tape, he wrote "Gift," just in case, he explained, the FBI started asking questions. He would also make presents of cameras, the disposable kind, because he thought it important we all hold on to memories.

Arnold also loved to drive around. He knew his way around town better than the most adroit cabbie, and every drive to the supermarket, where he insisted on pushing around his own cart, or wherever else, included a history lesson. As we sat in traffic in my VW Bug, which he called "Herbie," he would tell me stories about horse-drawn fire engines or the great molasses flood in 1919. Later, amazingly, he would e-mail me - one of his nephews gave him a computer - things he forgot along the way.

Other than the computer and an old TV,  both of which always had problems, Arnold lived in a cramped apartment strewn with cat litter. Paint peeled off the old, warped walls and the place hadn't seen a renovation since before man set foot on the moon. But he got along fine, shopping for himself, making his own meals, and scrubbing all his dishes. When he had the energy, he changed his sheets and did his own laundry. He also looked after his roommate Janna, an infirmed woman 30 years younger, who began renting a room from him and his wife in 1958, and never left.

both of which always had problems, Arnold lived in a cramped apartment strewn with cat litter. Paint peeled off the old, warped walls and the place hadn't seen a renovation since before man set foot on the moon. But he got along fine, shopping for himself, making his own meals, and scrubbing all his dishes. When he had the energy, he changed his sheets and did his own laundry. He also looked after his roommate Janna, an infirmed woman 30 years younger, who began renting a room from him and his wife in 1958, and never left.

As his 100th birthday approached, I asked Arnold what he lived for. "Burger King," he said at first, only partially joking. As much as he savored the hefty portions at soup kitchens, or the spare salads and cooked cabbage he served himself at home, he liked to go out to eat, often treating himself to baked potatoes at Wendy's or French fries at Burger King. When we went out together - his favorite place was the Old Country Buffet, which he loved for its all-you-can-eat buffet - it never failed to amaze me how much he could pack down, how second helpings often turned into fourth helpings. Arnold easily swigged more than five cups of coffee at each meal.

I pushed him for a more serious answer, and he said this: "Some people live for pretty girls. Some live to eat. Some like to go to the movies. I like all of those. But it's my friends that matter the most."

After all the years, I asked whether one lesson stood out, some piece of wisdom he most wanted to pass along. He looked at me intently and said: "To be more tolerant."

He also spoke of love.

"It's the biggest joy in life," he said. "There can't be too much love."

About three months before he died, Arnold complained about some pain, and I took him to the local Veteran's hospital. A test, his doctor told me, showed he had an advanced stage of bladder cancer. I found myself in an odd position, one I hadn't expected.

It was up to me to break the news.

I figured it was best to first ply him with something to eat, a muffin and a large coffee, which he devoured. When we spoke about the prognosis, Arnold never showed a sign of fear, nor did he ever lose his sense of humor. He favored aggressive treatment, he told me, and despite growing aches and pains, he wanted to live.

As he underwent nearly a month of radiation treatment, I watched in awe as he refused to complain and flirted with the nurses. When I asked how he felt, he insisted: "Fantastic … Excellent - with a capital K," a saying of his I never quite understood. Did he need or want anything? He'd smile and say: "Bring me a bag of gold."

A few days later, I called to wish him a happy birthday.  There was a long pause, and it sounded like he was struggling to hold the phone. Then I heard this: "Dave, I can't breathe."

There was a long pause, and it sounded like he was struggling to hold the phone. Then I heard this: "Dave, I can't breathe."

An ambulance took him to a nearby emergency room, one of countless elderly people rushed to hospitals on any given day for trouble breathing.

The night before, security guards had thrown me out of the same hospital for a story the paper assigned me to cover, a relatively routine event for me. This time I cleared past the guard station and found Arnold hooked up to an array of machines, with a huge breathing mask pumping oxygen into his lungs, now full of liquid.

All I could do was try to impress upon the doctors and nurses the preciousness of this man. Then, before his nephew and a friend from his church arrived, a resident asked me whether he should be resuscitated if his heart stopped, or if necessary, intubated with a ventilator.

I wasn't sure what to do - I had never conceived of having this kind of relationship with someone I wrote about for the newspaper. This definitely wasn't taught in Journalism 101.

Five days after his 100th birthday, I stood outside his room in the intensive-care unit and listened as nurses marveled at his improved health. Doctors suggested he might soon be well enough to return home. As I prepared to leave that afternoon, Arnold turned to me, and over the sound of pumps and monitors, he said, "I love you."

That evening, a nurse called. Arnold's heart rate climbed sharply. He had no more than 10 minutes to live, the nurse figured.

I raced to the hospital. When I arrived, the machines had been turned off and the tubes removed from his arms.

He was dead.

Alone with him, before his family and other friends arrived, I kissed his cold forehead and thanked him for prying open my heart, for showing me that poverty, old age, and disease doesn't have to sap spirit.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 3/30/2003

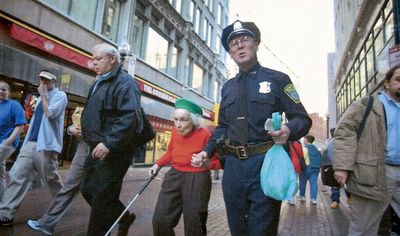

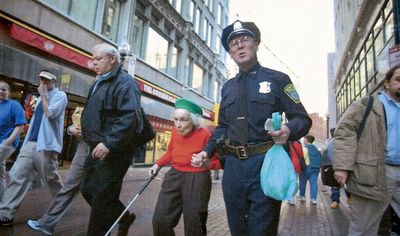

Every cop suffers his own indignities.

Peeling drunken men off sidewalks. Chasing thugs through crowded streets. Even helping an old, incontinent woman change her soiled sheets.

Some cops let it get to them. Too many violent nuts, too many insults, too many petty crimes not worth their time. Eventually they end up behind a desk, pushing papers in some musty precinct.

Not the man dispatchers call Alpha 633.

At 61, and one of the city's oldest cops still walking a beat, Officer J.J. O'Malley has become a one-man strike force, a veteran of the roughest streets who has his own definition of preemptive action. In a time of war, with security heightened at home, the short, stocky man in the blue polyester uniform disarms would-be wrongdoers -- his way, without handcuffs.

"I just give them a pat on the back, you know, talk to them a bit, and maybe ask, 'You're not a funny guy, are you?'" says O'Malley, who prefers not to make arrests. "I can be assertive. But I want people to respect me for me, not for my gun and walkie-talkie. There are enough bad guys out there, you don't have to be aggressive with everyone."

Over the past three decades, ever since the city fashioned the area into a pedestrian mall, the patrolman has become known as the mayor of Downtown Crossing. Chatty but vigilant, he keeps a close watch on the tens of thousands of people passing through daily, bonding with everyone from local lawyers to the homeless to tourists.

With Police Commissioner Paul Evans urging 100 officers to leave the force on voluntary retirement to avoid broad layoffs, it's unclear how much longer Alpha 633 will be on the beat.Long a fixture on the evening commute, O'Malley seems to know nearly everyone, as well as their business.

There's the aging prostitute with AIDS who robs her clients. The priest who plays the lottery and takes strolls around midnight. The 22-year-old who recently opened a high-priced hair salon, the Vietnamese guy who loves basketball, and the old man who makes crank calls from a men's room in Filene's.

After roll call one afternoon, he steers his cruiser through the neighborhood and parks it where he always does, just off the corner of Summer and Washington streets.It's a few minutes after 4, the time he's started work for the past 18 years, when he spots a homeless man in a jewelry store.

O'Malley approaches the man, smiles, and quips: "What are you doing, buying a new watch?"

The man laughs nervously, and before bolting, says defensively, "Nope, I'm just gonna go to the shelter early tonight."

Over the course of an average night, he'll respond to calls for burglar alarms and men passed out from guzzling Listerine. He'll also walk a blind 80-year-old woman home, escort the Cape Verdean manager of a fruit stand to her bank, advise the 19-year-old manager of a card store about the ills of smoking, and track down a phonebook to provide directions to lost South Korean tourists.

"He's the people's cop," says Sheila Jordan, a sales clerk at Tello's clothing store who has known O'Malley since he began the beat in 1979. "You ask some officers for help, and they won't do anything. To him, everything's important. He does things he doesn't have to do. That's why people respect him."

The list of his admirers includes the homeless who've been on the streets for years and hustlers whom he and his colleagues have spent months trying to bust.Near dusk he spots Dennis Gaskell, who spent 12 years on the streets of Downtown Crossing. The recovering alcoholic now drives a Cadillac and helps run the shelter where he used to sleep. "He would pour out our liquor and we wouldn't like it," he says. "But he always treated us respectfully, like human beings. Something you don't get from most cops."

Then there's Andre, the 21-year-old guy in flashy clothes, who for hours every day holds court on the corner by Bath & Body Works. Scores of young pals slap his hand, talk about music, and loaf around with him until dark. Through large bifocals, O'Malley watches Andre and says, "I'm sure he's up to no good."

But the man with the black clip-on tie and pointy blue hat takes a different approach from other cops, who've already hauled Andre into the precinct for suspicious behavior. O'Malley jokes with him and his friends, prompting laughs from one large man with a wild Afro when he tells him: "Get a haircut, man."

"I call him 'Officer Friendly,' " says Andre, who insists he's just hanging out in what he calls the "most entertaining part of Boston." "You could say he's like a role model. He's always taking care of the public. You've gotta admire that."

The amiable approach also works, even if O'Malley's not the only reason for the drop in crime.

Since he started commuting from his Lower Mills four-bedroom home, the number of violent crimes in Downtown Crossing has dropped by two-thirds, according to police statistics, and property crimes fell even more. Last year, for example, only 19 vehicles were either stolen or had such attempts made on them, while in 1979 there were 298. In the same time, the number of robberies and attempted robberies dropped from 221 to 46.

With rush hour past, most of the pushcarts gone, and the streets increasingly empty, he laments: "It used to be there was always something going on with all the clubs, pickpockets, and unruly people. Now, I have to check to see if my walkie-talkie's on at night."

Things have changed over the years. He gets half the 16 or so calls he used to receive on an average night, stopping in a bar for a beer is no longer allowed, and his bosses press him to wear a bulletproof vest and carry a gas mask in his cruiser, neither of which he bothers with.

He doesn't lament all the changes, of course.

For one, his pay has improved, from $118 a week when he started on the force 34 years ago to his current weekly salary of $953. Then there are all the friends, like the woman from the Chinese takeout kitchen who flags O'Malley over around dinnertime. Before he walks in, she heaps a generous serving of lo mein, chicken, and fried rice into a takeout box.

The cop can't resist. "They want to give me something," he says, stowing the food in a booth where he stays when it snows or rains. "If I don't take it, I insult her. And the truth is, I don't mind it."

Despite the many changes -- the influx of well-to-do residents and chic restaurants, the new brick walkways and improved lighting, the flourishing of chain stores -- the job's original lure remains: the great mulligatawny that makes Downtown Crossing.

In addition to cornerstones like the 203-year-old Stoddard's cutlery shop, the 164-year-old E.B. Horn jewelry store, and the 128-year-old recently refurbished Locke-Ober restaurant, the neighborhood's stew now includes more college students, living in newly built dorms. New high-rises sprout, like the Ritz-Carlton, as well as the new multiplex movie theater off Tremont Street.

"With all the change, it's nice to know something hasn't -- that Jim O'Malley is still here," says Karl Vulker, who owns the Winter Street Lottery and has known the officer for 15 years. "He's always here for us, always keeping an eye on things."

That will change, perhaps all too soon.

The aging officer, by department rules, will have to turn in his badge in 3 1/2 years -- if he resists the current voluntary retirement pressure. It might be nice to spend more time with his wife, and a grandson recently born to one of his three grown children, but it's a day he isn't anticipating.

Gazing at the golden dome of the State House, with a full moon rising and the late crowd making its way downtown, he inhales, taking in the strangely comforting chaos of the night.

"I don't really consider this work, and sometimes, I think, I can't believe they're paying me for this," he says. "Just look at all these people passing by. These are good people. They've all been places I've never been, and if you open up, you learn things. For me, I think this makes an interesting life."

He waves and jokes with an old friend, offers directions to a stranger, and eventually brings a homeless man to a shelter, persuading officials there to let the man enter, even though he'd been barred for some reason.

Nearly everyone he meets leaves with a smile.

Around midnight, with rats scurrying through the streets and the garbage trucks making the rounds, O'Malley climbs into his cruiser. He takes the long way back to the station, slowing as he passes the darkest alleys.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

A tale of one Meth dealer's rise and fall

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 05/07/2006

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 05/07/2006

By the time the law caught up with Dale Bernard, the paunchy addict was on the brink of homelessness -- far from the days when he spent weekends at the Four Seasons hotel and hoarded cash as a dealer of the potent, highly addictive drug he called "Tina."

This is a story of how the 43-year-old from Boston, whom a federal judge late last month sentenced to seven years in prison, managed an illicit connection long feared by local officials: While high much of the time, he built a bridge between California and Boston, importing a steady flow of crystal meth and feeding a growing problem here -- made visible in last month's bust of an alleged meth laboratory in Dorchester.

"He was a significant meth dealer selling substantial quantities," says Nancy Rue, an assistant US attorney, at his sentencing hearing at the US District Court in South Boston. "He was a meth addict who spread his addiction."

Over the past decade, methamphetamine has been mainly a West Coast phenomenon, but in recent years it has pushed across the Midwest and is increasingly competing with heroin on the East Coast.

In Boston, 75 people last fiscal year sought treatment for meth in local hospitals, up from 53 the year before, and compared with just five who sought treatment in 2001, according to the Boston Public Health Commission.

But while federal officials say more than 1.4 million people across the country used the drug last year, meth remains a relatively small problem in the Boston area. The euphoria-producing stimulant, which increases libido, still accounts for fewer than 1 percent of those seeking treatment in Greater Boston hospitals.

"We may not see it quite as severe in our area yet; nationally, it is a huge, huge problem," Tina Murphy, a special agent from the federal Drug Enforcement Administration's New England Field Division, said at a conference in February on the dangers of meth that city officials organized for local advocates. "In Massachusetts, the greatest threat is meth being shipped in from the West Coast."

Before finding himself the target of federal drug agents in 2004, before what he describes as years of sleepless nights, unprotected sex with too many gay men he met online, nearly being killed in a drug-fueled car wreck and being robbed at gunpoint in California, he graduated from Essex Agricultural & Technical High in Danvers and headed to Penn. State in 1981, according to school records.

Raised in an upper-middle-class family in Andover, Bernard got along well with his family, who accepted his homosexuality when he came out at age 16. His mother says he regularly attended church, never got in trouble, and stayed away from drugs, aside from trying pot once.

"He was a good kid," says his mother, Carole Bernard, who still lives in Andover. "I didn't really know what was going on."

His drug problems started, he says, when he stopped believing in God. A few years after he dropped out of Penn. State, a robber armed with a .22-caliber handgun burst into the Brighton leather store Bernard managed and shot him in the stomach. The bullet shattered Bernard's faith as well.

He spent about a week recovering at Brigham and Women's Hospital, he and his mother say, much of it on morphine. When he left, he yearned for something to kill the pain. "The morphine felt so good," he says. "I needed something to replace it."

In a world where God no longer existed, he figured: "I might as well enjoy myself."

Shortly after, a friend introduced him to cocaine. "It didn't take the pain away," he says, "but it made it so I didn't care about it."

For a decade, Bernard balanced work with a low-level addiction to White Russians and cocaine, he says, but his real problems didn't start until 2000, when he fled the local drug scene and landed in that of Los Angeles.

Two weeks after arriving, Bernard met someone on the Internet looking to "party-n-play," and he had his first experience with the little crystals. His new friend taught him how to ignite the crystals with a blowtorch lighter and suck the vapor from a glass pipe.

Euphoria washed over him. "I felt amazing, invincible, like the most attractive person in the world," he says.

The benefits, to his mind, included reduced appetite -- the 6-foot-3-inch addict says he dropped from 250 to 180 pounds -- needing little sleep, and having increased sexual energy.

A few months later, Bernard lost his job and found a new way to pay his rent and feed his addiction: He bought larger quantities of meth and sold what he didn't use for a profit.

Then one day, Bernard says, he came home and found himself face-to-face with a 9mm gun, held by one of his initial suppliers. He says they tied him up, ransacked his apartment, and carted off all his possessions in his Dodge Ram pickup.

The experience, nearly two years after moving to LA, provided enough incentive to return home, where his parents took him in and he made an effort to stay clean. The effort lasted about a month, until a friend in LA sent him his clothes. Bernard found an "eight ball" -- an eighth of an ounce of meth -- in a pants pocket. He stared at it, and let a day go by.

Lonely, empty, and sick of having little energy, he couldn't resist. "It was right there in my hand," he says. "I missed the money, the fast pace, the sex."

The rush lasted an entire day, and soon after, he moved out of his parents' home to an apartment near Boston Medical Center, where it all started again.

He contacted his old suppliers on the West Coast, he says, and they shipped him packages filled with coffee bags, the meth hidden inside, wrapped in cellophane. He bought by the ounce, which he says cost him a minimum of $1,400. He would sell an ounce for as much as $3,500.

He says he bought digital scales, special safes, and a stash of Slurpee straws from 7-Eleven, which he used to separate the crystals. His business quickly grew to about 50 clients, he says, most of whom he met online. "Sex was my marketing tool," he says. "If they smoked with me and had sex with me, then they weren't a cop."

Aside from his fillings falling out (meth rots teeth) and the need to stay high constantly -- he says he smoked an eight ball a day -- he was living large. He says he bought an Infiniti I-30, rented a new three-bedroom apartment, bought his live-in partner a car, and took him on a cruise to the Caribbean.

Then some of Bernard's associates were arrested. Business slowed, money got tight, and Bernard felt he was being watched. He chalked it up to paranoia.

But DEA agents had been following him for nearly a year. They collected Federal Express receipts and meth-lined plastic bags from his trash, recorded his calls, and discovered the CD cases and shrink-wrapped jewelry boxes where he hid his meth, according to a sworn statement by the lead DEA agent. They had informants record his conversations, in which he described his Malden apartment as "the crystal palace, the house that Tina built."

With enough evidence, and Bernard on the brink of homelessness, federal agents arrested him in Malden on June 2, 2004.

"I observed there was no electricity or power at the residence," wrote Michael P. Cashman, the DEA special agent who investigated the case, in his report on Bernard's arrest. "I spoke to the landlord, who stated that he was in the process of evicting Bernard for nonpayment of rent."

Before Bernard pleaded guilty last year to conspiracy to distribute meth and six counts of distribution, he spent about a month at the Norfolk County House of Correction in Dedham. A judge sent him to a Cape Cod detox facility, and after five months there authorities allowed him to move to the first of three sober houses in Malden, where addicts are tested for drugs every week.

In the time between his arrest and sentencing -- when authorities sought information from him to implicate other dealers -- Bernard struggled to overcome his addiction. "The strongest pills I take now are ibuprofen," he says.

He restored ties with his family, church, and to the idea that he could live without drugs. He went to therapy, readily acknowledged his addiction, and for the past year managed to hold on to a job as a travel agent.

"He's come a long way," says Billy Maragiogilo, executive director of New England Transitions, who runs the sober house where Bernard lives. "He's complied with all the rules -- three drug tests a week, a house meeting a week, and three AA meetings a week. He's helped out other guys in the house. We have no complaints about him."

Still, Bernard would hear Tina's call, in his dreams or when someone recognized him on the street and offered him a hit.

"My addiction is still there," he says. "I still feel it, the desire to get back into the lifestyle. . . . But I know if I kept going the way I was going, I'd probably be dead by now."

Last month, after US District Court Judge Joseph L. Tauro sentenced Bernard to 87 months in prison and five years of probation, Bernard dropped his head, and his eyes reddened with tears. Though he had faced a potential $4 million fine and as much as life in prison, he had hoped, as his lawyers argued, that his efforts to pull his life together might keep him from going back to prison.

He starts serving his sentence next week.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

DO NUMBERS BELIE A GROWING PROBLEM?

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 05/07/2006

The federal Drug Enforcement Administration found only three meth labs in Massachusetts last year. In all of 2004 and 2005, DEA agents say, they submitted just 20 meth samples from the Boston area to state labs. Patients seeking treatment for meth overdoses account for fewer than 1 percent of all treatment admissions, local hospitals report.

But officials say the numbers are deceptive.

"The gap is partly because many users aren't seeking help, and the main way we measure use is by people asking for help or seeking treatment," said John Auerbach, executive director of the Boston Public Health Commission. "My sense from reading reports around the country is that the problem went from being below the radar to being enormous in a number of areas. People began paying attention to it only when it became visible, which is why we're taking it very seriously now."

Auerbach and treatment providers say accounts from patients and doctors suggest the problem is spreading beyond the city's gay community, where the drug has hit the hardest. Of about 300 patients last year who sought acupuncture detox at Fenway Community Health Center, one of the city's largest substance-abuse programs for gay men, 30 percent described crystal meth as a "primary" or "significant problem" up from 12 percent in 2003.

"We're seeing the tip of the iceberg," said Will Halpin, a clinical social worker at Fenway's mental health and addictions department. "The ER visits and treatment visits just aren't really representing the reality. I think it's only a matter of time before we reach a threshold where people are really seeking treatment. I think when outside forces child welfare, police agencies start recognizing the problem, you'll see more people seeking treatment."

Michael Botticelli, assistant commissioner for substance-abuse services at the state Department of Public Health, is also concerned that meth use in the Boston area is on the increase.

"Clearly, there's an eastward march of crystal meth, and we're concerned it will take hold here," said Botticelli. While the drug's abusers "may represent a small percentage of our treatment admissions, when we look at the urban gay community, it gives us pause. We're seeing a substantial percentage of our admissions among urban gay men, and there's an impact there."

At Victory Programs, a substance-abuse program in the city where about 1,200 people last year sought treatment, officials say meth use is a problem for a growing number of their patients and is no longer confined to gay men.

"I think there's a huge gap between official statistics and the reality," said Jonathan Scott, the program's president and executive director. "I feel like meth use in the city is catastrophic, and we're seeing a real cross section of users now. It's not just a gay drug anymore."

He blamed the state Department of Public Health for not including meth on its intake forms for substance abusers until last year. Victory Programs also only began closely documenting meth use last year. Of 272 men and women in the program's residential-treatment homes, about 7 percent of men and 4 percent of women said they had used meth.

"When you don't have the vocabulary to track or define something, it has the effect of making it seem nonexistent," Scott said. "It's only when you create the vocabulary to identify something that you know it's there. So we have to go on anecdotes."

He likens meth users to late-stage alcoholics who suddenly find themselves bereft of family, jobs, and homes. The difference, he said, is that alcoholism is more of a progressive disease that can take decades to wreck someone's life; meth often leaves abusers in dire straits in a year or two.

"In 30 years of drug treatment, because of meth, I'm seeing people with no experience using drugs coming in with brain damage and psychological damage that is irreparable," Scott said.

"With meth addicts, we see an incredible acceleration of the disease model. I think we're at a stage reminiscent of when HIV was emerging. We're starting to see it grow."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 12/04/2005

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 12/04/2005

BROOKLINE -- Haircuts always involve a bit of a gamble.

For the women who sit before Sandra Darling, there's often more at stake than their vanity: One errant snip could mean the loss of an investment worth thousands of dollars

"Once you cut it -- that's it," says Darling, her long, slender fingers as important to her as to a surgeon. "It's not growing back."

The 26-year-old hairdresser has built a business in recent years cutting, washing, and styling sheitels -- wigs -- worn by local Orthodox Jewish women, whose religion requires that no man other than their husband sees their natural hair.

The custom, intended for centuries to signify modesty and chastity, has definitely evolved.

The old bushy wigs -- often made of artificial material or coarse horse hair -- have given way in recent decades to the French top, the layered look, and the feathered cut, among others, nearly all fashioned from human hair imported from Europe.

And they're anything but matronly.

They come in all shapes, sizes, colors -- and prices. Orthodox wives can be blondes, brunettes, or redheads, with bangs or curls, wavy or straight hair, though most try to match the color of their natural hair, Darling and others say.  (Many often have several wigs, for formal occasions, daily chores, and synagogue.) The permutations allow them to affect a short, spiky look, a frumpy and disheveled mop they can connect to hats or headbands, or a long, sultry mane more lustrous than their own hair.

(Many often have several wigs, for formal occasions, daily chores, and synagogue.) The permutations allow them to affect a short, spiky look, a frumpy and disheveled mop they can connect to hats or headbands, or a long, sultry mane more lustrous than their own hair.

The elegance and expense of the pieces arguably contradict the tradition's purpose: Darling and Orthodox Jews interviewed say that sometimes they find the women's natural hair less attractive than their wigs.

Women may spend weeks or longer shopping for their wigs before their wedding, and they can cost as much as $5,000, they say. Wigs are now available on websites such as http://www.savvysheitels.com/, which includes adver tisements with come-hither models wearing bright red lipstick.

So when the women visit Darling, who's Catholic and learned only in 2001 about the Orthodox wig tradition, they often know exactly what they want. "They're very to the point -- and they can be stubborn," she says. "A wig might be made to go to the left, and they want it to go to the right. I'll do it their way, but I'll show them it doesn't work."

Over the years, Darling says she has cut more than a hundred wigs and styled thousands of others. She began nearly five years ago when a young brown-haired woman dropped in at her Brookline salon and asked for a trim.

"I just want to let you know it's a wig," the woman announced, recalls Darling, who wasn't sure what to do, but knew that if she messed up it was going to be an expensive mistake. "I had butterflies," she says.

Since then, Darling has learned there are differences between cutting wigs and natural hair. Wigs take about a half-hour longer, she says, and she can charge about twice as much, usually $50 for a cut and $25 for styling. The women require privacy, and she ushers them into a private room in the back of the salon, Crew International on Harvard Street, where they open their carrying cases and remove their wigs from a mannequin's head.

Darling often does three during one appointment, she says, using special clips and an elastic band that stretches from one ear to another. She has to be careful the wig does not fall off her client's head while she's working. Treating the wigs like natural hair, she shampoos them, sets some in curlers, colors others, and blow-dries most when she's done.

The only hairdresser in her salon and one of a few in the area with such a skill, Darling has no need to advertise. "Word gets around very quickly," she says. "They talk in the synagogue, I guess."

The talk sometimes also revolves around whether the women are really required to wear wigs, and what constitutes an appropriate source for them. Last year, after rabbinical authorities in Jerusalem ruled that wigs from India weren't acceptable because they might have been used in Hindu ceremonies -- thus making them potentially idolatrous -- hundreds of Jews in Brooklyn thronged into the streets, piled up the condemned wigs, and torched them.

Before Harvard graduate students Aviva Presser and Erez Lieberman  married three months ago, the Orthodox Jews discussed whether she would wear a wig. In the end, Presser decided to buy one, but the 24-year-old says she rarely wears it more than once a week, generally only to synagogue. The rest of the time, like others, she wears a hat to cover her hair.

married three months ago, the Orthodox Jews discussed whether she would wear a wig. In the end, Presser decided to buy one, but the 24-year-old says she rarely wears it more than once a week, generally only to synagogue. The rest of the time, like others, she wears a hat to cover her hair.

"It's way less comfortable than a hat," says Presser, who cut her long, brown wig on her own. "I'm sort of debating and learning more about the practice. It's the Jewish law obligation, but I want to establish whether God cares. If I find it's an invention of people, I guess I'll be less inclined."

Presser dated men who would have ended their relationship immediately had she said she wouldn't cover her hair, she says. In an interview after Shabbat services on a recent Friday night at Young Israel of Brookline, her husband said it's not a big deal for him. "It's entirely up to her," he said.Not all Orthodox husbands have such liberal views.

"I stick to the halakhah," or Jewish law, says Shlomo Amar, who married six months ago. "The hair of a married woman is considered an attractive part of her body and needs to be covered."

He and his wife, Rochelle Amar, also recently attended services at Young Israel, where she was wearing a fashionable wig parted in the middle. The soft, shoulder-length brown hair from Eastern Europe, which required several days to pick out, looked naturally shiny, and matched her eyebrows.

She doesn't like to wear it too often, she says, because she worries it might ruin her natural hair, which most women hide beneath their wigs with the help of barrettes and netting. "That would defeat the purpose," she says. "Then I might not be beautiful for my husband."

Does she think it's potentially hypocritical to wear a wig that some might find attractive?

She's not concerned.

"Just because the law requires modesty," she says, "doesn't mean you have to be ugly."

Her husband says he would object if he thought her wig were too extravagant.

An Orthodox rabbi for eight years whose wife also cuts and styles wigs, Rabbi Yitzchak Rabinowitz of Congregation Beth Israel of Malden says, "There's no question that some women overdo it."

But he also says there's no reason why an Orthodox woman can't look nice, and the mere wearing of a foreign object to cover her "crowning beauty" fulfills her obligation."

According to Jewish law, a woman is not supposed to go around dressed in a provocative manner, where so much of her body is uncovered, like a low-cut dress," he says. "If a woman covers herself properly, is it a contradiction if she wears something attractive to cover herself up? It's not."

It's a sentiment Sandra Darling holds dear.

On a recent afternoon at the salon, with bouncy music in the background, glossy magazines in the waiting area advertising skin-baring celebrities, and Christmas decorations on the walls, Darling says she doesn't question whether her clients should be concerned about primping their wigs.

"Whatever makes them happy," she says.

Not anything goes, though.

"I won't let them look stupid."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com

Copyright, The Boston Globe

For decades, two forces have clashed over who should guide large ships into Boston Harbor. Now, with business down and security fears up, they're trying to rewrite the law in their favor (Click here for a slideshow.)

For decades, two forces have clashed over who should guide large ships into Boston Harbor. Now, with business down and security fears up, they're trying to rewrite the law in their favor (Click here for a slideshow.)

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 5/07/2006

In the darkness before dawn, with waves rising 7 feet and a cold drizzle falling, the veteran seaman balances his 48-year-old legs on the bow of the bobbing pilot boat. Through a stiff wind, he reaches into the fog for a grease-covered rope ladder, which dangles off the starboard side of a 600-foot oil tanker.

The steep climb aboard the Panamanian-flagged Alpha Express doesn't rattle Marty McCabe, who over the years has made hundreds of such ascents, many in storms with seas more than twice the size.

"When you step on that ladder, you trust everything is prepared properly," says McCabe, noting ship crews often lower the ladder only minutes before he boards, to keep the typical 25 feet of rungs from icing up. "No boarding is routine. As soon as you consider it routine, that's when something happens."

A former tanker captain who has guided ships from the Mississippi River to the South China Sea, McCabe is one of 10 men who make up the Boston Pilot Association, a 223-year-old institution founded and regulated by the state to help bring large vessels -- those with hazardous cargo or weighing 350 gross tons or more -- through the shoals and fast-moving currents of Boston Harbor.

For decades, the pilots, who earn as much as $250,000 a year, have routinely passed control of at least 90 percent of the ships they board at sea to docking masters, specially trained tugboat captains who climb aboard in the inner harbor, take the helm as the ships enter narrow channels, and use a team of tugboats to guide them to port. The custom, never a legal requirement, has been an option for the ship owners, who often pay hundreds of dollars extra for the docking masters' assistance.

But as the area's ports have lost business and security concerns have grown in recent years, the peace has begun to unravel. Late last year, lawmakers on Beacon Hill proposed a bill that would require every ship coming in to port to have a docking master on board.

Docking masters argue it's a safety issue: They're better trained than pilots at operating ships in tight spaces and more skilled, they say, at orchestrating the minuet of tugboats, three to five of which surround most large vessels entering the harbor.

Harbor pilots counter that safety is already best served: It's misleading for docking masters to suggest they're more qualified, say the pilots, who, unlike docking masters, are required by state law to hold an unlimited ocean master's license, the top Coast Guard credential for operating ships. Mandating docking masters, they worry, could lead to lawmakers deeming their jobs redundant and put lesser-qualified seamen guiding ships into the harbor.

Over the past year, Boston Towing & Transportation Co., which employs seven of the harbor's eight docking masters and controls about 75 percent of the local tugboat business, has spent more than $150,000 lobbying to pass the law. The company already requires all ships using its tugboats to hire its docking masters, meaning few tankers today are taken to port by pilots. Company officials point to an incident last month involving a pilot guiding a 600-foot salt carrier with three tugboats from another company. The pilot overshot his dock at the Boston Autoport in Charlestown and came close to striking a pier at the Exxon terminal in Chelsea. The pier, about a half-mile away and on the opposite side of the Mystic River, abuts the liquefied natural gas terminal in Everett.

"I've never seen anything like that before," says Jake Tibbetts, president of Boston Towing, which helped publicize the incident by providing pictures and a video to the Coast Guard and local media. "You need someone who knows what a tugboat can do, and what it can't do. We're the experts at handling ships in close quarters. All it is is a safety issue. How can you be against a safety issue?"

Some lawmakers, including those who have accepted campaign contributions from lobbyists representing Boston Towing, used last month's incident to urge colleagues to pass legislation supporting Boston Towing's goals.

"We need to make sure that we have the right people at the right time guiding the ships in and out of the harbor," says Senator Bruce Tarr, a Gloucester Republican who served as cochairman of a harbor piloting panel. "When a vessel with hazardous cargo is transiting through a sensitive area, my bias would be to require a docking pilot."

Last year, Senator Jarrett T. Barrios, who like Tarr has accepted contributions from former state Senator Robert Durand, currently Boston Towing's lobbyist, proposed a bill requiring docking pilots aboard all ships ferrying hazardous cargo into the harbor. But it failed to gain enough support. Barrios, who backs a plan to revive a version of the bill in coming weeks, called last month's incident a "red flag" and argues it underscores the need for stringent background checks and licensing requirements for docking masters, whose job now requires no formal license.

Last year, Senator Jarrett T. Barrios, who like Tarr has accepted contributions from former state Senator Robert Durand, currently Boston Towing's lobbyist, proposed a bill requiring docking pilots aboard all ships ferrying hazardous cargo into the harbor. But it failed to gain enough support. Barrios, who backs a plan to revive a version of the bill in coming weeks, called last month's incident a "red flag" and argues it underscores the need for stringent background checks and licensing requirements for docking masters, whose job now requires no formal license.

"Just like airline pilots got additional scrutiny after 9/11, individuals who can guide a ship using hazardous materials as an object of terror should be regulated in the same way," says Barrios, a Democrat who represents communities along the Mystic River and chairs the Joint Public Safety and Homeland Security Committee. "We have to know we've done our best to minimize accidental collisions or some nefarious scheme to injure or terrorize."

Grand Central harborBoston Harbor can be a busy place, with local ports each year receiving more than 1.3 million tons of cargo such as automobiles, 12.8 million tons of fuel, and 210,000 cruise ship passengers, according to the Massachusetts Port Authority.

With thousands of ships plying the harbor's waters every year, there are scores of incidents, or what the Coast Guard calls "marine casualties," that have resulted in injuries or other damage. Between January 2000 and March 28, 2006 in Boston Harbor, the Coast Guard recorded two deaths and 17 injuries aboard vessels, 12 boat sinkings, 25 accidents when a vessel struck an object such as a bridge or buoy, nine collisions between vessels, seven groundings, and 155 incidents that led to environmental damage, such as oil spills.

Still, pilots, port officials, and others in the shipping industry argue that the proposed legislation is unnecessary. The existing regulations have worked for decades, they say, and there's no safety or security reason to require docking masters aboard ships already controlled by pilots.

"We've all been ship captains -- no docking master can meet that criteria," says Gregg Farmer, president of the Boston Pilot Association, who argues the pilot aboard the carrier ship that drifted off course last month responded professionally to strong currents. "We're as qualified as a mariner can be. This whole thing is really a tugboat competition."

Other local tugboat operators -- there are two other companies in the city -- argue the proposed law really serves as a way for Boston Towing to lock up more of the harbor's tugboat business. One of the companies, Constellation Tug Corp., employs a docking master, but both often rely on the pilots to coordinate their tugs to guide ships to port.

"Are we docking tugboats or are we docking ships?" says Marc Villa, president of Constellation, which owns five tugs compared to Boston Towing's 11. "The real issue has to do with whether or not the harbor pilots are to be considered docking masters. They should be considered docking masters, as they are from Fall River to Newport. The pilots are the most professional individuals in the harbor, and we're confident enough to use them."

More safe, or less competitive?

Others in the shipping industry worry that legislation requiring docking masters would make local ports such as Conley Container Terminal and Black Falcon Cruise Terminal less competitive.

They cite examples such as Volkswagen, which four years ago shifted shipping 82,000 cars a year from Boston to Rhode Island because of a local harbor tax, and Maersk-Sealand, which in 2000 dropped Boston as a trans-Atlantic port-of-call, at the time cutting 25 percent of the port's container cargo.

"If a bill is passed, the marketplace would no longer drive the costs," says Richard Meyer, executive director of the Boston Shipping Association, an advocacy group representing agents and many of the container and cargo shipping companies that use the port. "The fear is that a new legislated requirement will be an unnecessary increase in costs."

For similar reasons, Michael A. Leone, director of the Port of Boston for Massport, opposes new regulations. "No one has demonstrated for me that there's a need to change," says Leone, calling the port's safety record "very good." "Until I see a study documenting a need to regulate it, or I have customers calling us and asking for legislation, I don't think a statute is necessary."

Coast Guard officials -- who say their investigation into last month's near-hit of the Exxon pier hasn't revealed any negligence -- say laws outlining licensing requirements for a docking master could be useful, so long as they don't bar pilots from docking ships. It's now up to tugboat companies as to who qualifies to become a docking master.

Coast Guard officials further insist local politicians are wrong to say existing regulations are insufficient to protect the harbor's safety and security. To obtain a Coast Guard license to operate a tugboat or ship, they say, applicants must pass proficiency tests, be fingerprinted, and have their backgrounds checked by the FBI as well as local and state agencies.

Also, they say drug tests are required for any tugboat captain, docking master, or pilot involved in an incident leading to property damage in excess of $100,000, an injury that requires medical treatment, or a discharge of 10,000 or more gallons of oil.

"It's inaccurate to suggest that we don't adequately examine or check the mariners we license," says Captain James L. McDonald, commander of the Coast Guard in Boston. "My experience with both docking masters and pilots is that they are very capable and professional. From time to time, there will be errors in judgment, but I think anyone with the requisite experience should be able to work as a docking master. There shouldn't be a monopoly."

For Marty McCabe and the pilots, who this year paid local lobbyists $24,000 to press the Legislature to approve an 11 percent raise in their fees, the politics disappear once they arrive on the bridge of a ship.

On a recent morning, McCabe boards the pilots' 53-foot twin-diesel engine boat at 4 a.m. and takes a bumpy ride 12 miles to sea to meet the Alpha Express, which turns leeward to reduce the force of the 11-knot winds as he climbs the ship's ladder.

He has already checked the tides, the currents, and the winds, and after shaking hands with Korean captain Yh Bag and Filipino crew aboard the Japanese-made ship, he orders the helmsman to point the vessel southwest, toward the Citgo terminal in Braintree.

In a foggy sunrise that reduces visibility to little more than a mile ahead, he guides the ship and its 190,000 barrels of gasoline through an array of buoys along Nantasket Roads and the 300-foot-wide passage of Hull Gut.

"Each time we go down this, it's a different trip," he says.

An hour before the voyage ends, three Constellation tugboats surround the tanker, and Chris Deeley, the harbor's only docking master who doesn't work for Boston Towing, climbs the ladder and shakes hands with McCabe on the bridge.

It's an amicable exchange of the helm, and the 41-year-old former tugboat captain begins barking orders on walkie-talkies to his three tugs. The powerful, smoke-spewing boats cruise alongside the 106-foot-wide ship and nudge it through the Fore River Bridge, which is just 170 feet wide.

"It's like driving a Mayflower van through Beacon Hill without any brakes," says Scott MacNeil, an apprentice pilot aboard the ship.

When the tanker finally slows to a halt, the smell of gas pervading every crevice of the ship, the crew lugs the mooring lines in place, and the captains make the steep ascent off the ship and onto dry land.

The next day, they'll do it all over again.

E-mail David Abel at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

Sidebar:

ONE SUNNY APRIL DAY NEAR THE LNG TANK, A CLOSE CALL ON MYSTICA 600-FOOT SHIP OVERSHOOTS DOCK, AND CHARGES FLY

By David Abel

Globe Staff

05/07/2006

From a video of the incident, it appears a 600-foot salt carrier came only a few feet from crashing into the Exxon pier in Chelsea on a sunny Monday last month, in potentially disastrous proximity to the nearby liquefied natural gas terminal in Everett.

No one disputes that the pilot-guided Hato had drifted off course, to the opposite side of the Mystic River, about a half-mile away from its intended dock at the Boston Autoport in Charlestown.

But that's about all that's not disputed by the harbor's vying factions of mariners.

"He was totally out of control," says Jake Tibbetts, president of Boston Towing & Transportation Co., which used video taken by one of its tugboat operators to portray harbor pilots as inferior to their docking masters. "This wouldn't have happened in a million years if it was one of our guys."

Tibbets and his men insist the incident reflects why the Legislature should pass a proposed bill requiring docking masters aboard large ships entering the harbor.

"This is all about setting standards," says George Lee, Boston Towing's head docking pilot. "When you put your child on a bus, who do you want driving that bus -- an experienced professional, or someone else?"

Frank Morton, the pilot guiding the Hato, calls the video "propaganda" and part of Boston Towing's "goal of taking total control over the harbor."

"If they thought we were in trouble, why didn't they offer to help us, instead of taking pictures," he says. "How professional is that?"

Morton, 50, who has worked as a pilot for the last 15 years and has guided hundreds of ships through the Mystic River, acknowledges that he should have made a sharper turn as he crossed under the Mystic River Bridge.

But he says the large ship never came closer than 200 feet to the Exxon pier. The problem, he says, was that the ship got caught in the outgoing tide.

A strong current from the Mystic River caught the bow of the Hato, he says, while another current from the Chelsea River caught the stern, pushing the ship toward Chelsea.

Morton says he tried to steer the ship in the opposite direction, with the help of tugboats operated by Constellation Tug Corp.

But as the starboard-side tug pushed the ship from a right angle, he says, it came close to hitting a buoy and had to break off.

"That changed the whole nature of the job," Morton says.

So the pilot says he decided to take the Hato upriver -- away from the Autoport -- to come around for another try, which he did.

With the tugboats in place, he eventually guided the ship to port.

"It wasn't a pretty docking; it was a missed approach, in what we call the bailout area," says Marc Villa, Constellation's president. "Captain Morton acted prudently. If there wasn't such intense competition and proposed legislation, there wouldn't be someone standing around taking pictures. I think Captain Morton has been unjustly criticized."

Coast Guard officials investigating the incident say there's no evidence the Hato or any of the tugboats hit a buoy or the Exxon pier, as Tibbetts and others at Boston Towing have charged.

"Nothing happened," says Lieutenant Edward Munoz, senior investigating officer of the Coast Guard in Boston. "From a legal perspective, it's a non-incident."

Munoz also says his investigation has revealed "no evidence of negligence."

"It wasn't an ideal landing, and it's definitely not normal for a ship to drift that far off course," he says. "But I don't think the vessel was out of control, and just because the vessel might not have been doing what he wanted, it wasn't negligence."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 4/30/2006

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 4/30/2006

At an hour when lampposts carve shadows over empty streets, when geese outnumber people on the Esplanade, skunks troll through Brookline, and rats prowl around Beacon Hill, Tom Goulet is out sweating, his muscles burning, his mind far from shutting down.

Which for most people, given the time and his obligation to be up for work at dawn, would be the logical thing for the mind to be doing.

Nearly every night of the week, come rain, snow, or howling winds, the 48-year-old venture capitalist from the North End laces up his sneakers, tucks a cellphone in a fanny pack, and joins an unallied cabal of midnight runners.

"It's almost as peaceful as sleeping," says Goulet, a father of three. He says he often sees dozens of other late-night joggers but on a recent midnight run seemed to have the city to himself. "It's really beautiful to be out here on your own. It's nice and strange to feel the stillness of the city. It feels like a postcard."

Goulet and his seemingly cracked comrades in reflective shoes say they're aware of the risks -- close encounters with menacing denizens of the dark, or drivers failing to spot them darting through intersections, or anything from slipping on black ice to turning an ankle in an unseen pothole.

They also don't heed the advice of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, which counsels people to avoid strenuous exercise for as much as six hours before sleep.

"The idea is to prevent the body from producing endorphins and stimulants that can disturb sleep or lead you to wake up in the middle of the night," says Kathleen McCann, an academy spokeswoman. "Increased levels of hypocretin resulting from exercise at night can lead to awakenings at night."

Some scholars who have studied late-night exercise take exception to the academy's advice. They argue that people such as researchers, graduate students, and medical professionals who work irregular schedules -- in short, many people in the area -- are better off running late at night, when it's often most convenient.

Shawn D. Youngstedt, an assistant professor in the department of exercise science at the University of South Carolina, has overseen two studies that found late-night exercise does not impair sleep. In some cases, he says, it even helps.

One of his studies, published in the journal Physiology and Behavior in 1998, found that of a dozen college students who exercised on a stationary bicycle for an hour a half-hour before bed, none had trouble falling asleep. The other study, published a year later in the journal Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, found that of 18 college students who rode a stationary bicycle for three hours a half-hour before sleep, none had problems sleeping.

Lucas Woodward's most serene runs usually come after midnight, often in the dead of winter just after a snowstorm. With few cars on the road and a heavy stillness in the dry air, he says, there's something transporting about the quiet, especially after a long day.

The 22-year-old computer technician from Jamaica Plain often jogs around Jamaica Pond late at night, when it is pitch black save the distant streetlights and the odd car in the distance.

"At night, the wind dies down, and when you're all alone you can hear every footstep," says Woodward, who, like Goulet and other midnight runners, says he has no trouble falling sleeping afterward. "It's really peaceful."

But running in the middle of the night can have its awkward moments, particularly in Boston.

Their company, aside from nocturnal animals, occasionally includes drunken students spilling out of bars from the Back Bay to Brighton. There's also the homeless, who tend to stare at late-night runners as if they're creatures from another planet, and the cars that slow down, their passengers ogling the odd characters coursing through the dark. Even cats wandering the streets stop and gaze at those intruding on their solitude.

"It's socially unacceptable to exercise at night," says Woodward, a recent Boston University graduate who doesn't worry about lurking danger. "People look at me with the strangest expressions, but I feel like I can outrun anyone."

Some runners say they understand the allure of jogging late at night, when the streets are so empty that it feels safe enough to run in the middle of the road. But they advise against it.

Four-time Boston Marathon winner Bill Rodgers has run several late-night races, including midnight dashes through Sao Paulo, Brazil, and champagne-strewn courses in Manhattan's Central Park. For competitors, he says, it's usually best to run early in the morning, when muscles have had a chance to rest.

"At the end of the day, your body wants to rest," says Rodgers, 58. "It's also a lot easier to trip at night."

When Hal Higdon served in the Army 50 years ago in Germany, he often ran through the Black Forest at night, the moon his only light. The 74-year-old veteran of 18 Boston Marathons and author of "Boston: A Century of Running" says he now prefers to run under the sun. "Safety is a serious issue," he says, urging night runners to keep their iPods at home.

Others argue that it's safer to run at night, particularly during the summer or in warmer climes.

For Bob Loewenthal, a 73-year-old retired attorney from Atlanta, there are certain times of the year when running in the day is too dangerous. In the summer, when the temperature soars above 90 degrees, he starts his long runs around 3 a.m.

"During the day, I can have running company; I can see where I'm going; I can watch the scenery; I don't have to adjust my meal and sleeping schedule," he says. "Unfortunately . . . I must start a long run at the time that everyone else is sleeping in order to avoid the heat."

On a recent night in Boston, heat isn't the problem. With cold, stiff winds blowing off the Charles, Dan Laskey and Matt Webster lumber through Brookline toward the river, the lights of the skyline melting into the dark water.

At 12:30 a.m., their faces flushed less than a mile into the run, the 22-year-old roommates from Boston are wide awake. Morning, when they both have to be at work, seems far away.

"It's a good way to end the day," Laskey says.

Webster adds: "It beats watching TV."

Then the two disappear into the night, the reflective decals on their shoes slowly fading in the pale moonlight.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

Peru: Suite 511 THE NETHERLANDS? DOWN THE HALL. MEXICO? TRY NEXT DOOR

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 04/23/2006

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 04/23/2006

On the sixth floor, a door opens and merengue pulses from a stereo. A dozen men and women wait next to a large picture of the Dominican Republic's president, Leonel Fernandez, wearing the red, white, and blue presidential sash, which faces three black-and-white portraits of the island nation's founding fathers and a map of Hispaniola that lops off Haiti, its neighbor and historic adversary.

Sitting there in the Dominican consulate one recent morning, Felix Almonte smiles. The 47-year-old from Santo Domingo, who has lived in Charlestown and worked in supermarkets over the past eight years, doesn't mind waiting for officials to renew his passport amid the pictures of Pedro Martinez, the music, and the dropped s's of his nation's rapid-fire Spanish.

"When I come here," he says, "I feel like I'm entering my country. This is my culture. It's nice to be here."

Through the glass doors, past the potted plants and the low-rent awning, scattered among the offices of lawyers, mortgage brokers and psychologists, the building at 20 Park Plaza is where the Dominican Republic and five other countries post their emissaries -- more than anywhere else in New England.

Call it Boston's Embassy Row.

Unlike the gilded mansions and multimillion-dollar compounds in other major cities, here the consulates are stationed above storefront fast-food shops and behind unadorned taupe doors marked by small plaques that scarcely hint at the worlds behind.In Boston, a capital of medicine and academia, the consulates look as grand as dentists' offices.

"This is kind of a mini United Nations," says Jeff Ross, an immigration attorney who works in the building, which abuts the Park Plaza Hotel.

Behind one door on the 14th floor, at the end of a carpeted hall, hundreds of people -- young mothers breast-feeding their babies, prisoners waiting to be deported, local residents seeking visas -- stand in long lines at the Brazilian consulate listening to instructions in Portuguese.

Four floors below, two security cameras keep watch from above the first of three doors required to enter the Israeli consulate. Inside, two men trained to kill pat down everyone who enters, even those who have worked there for years. Then, before visitors can pass through specially built doors, they must walk through a metal detector.

On the fifth floor, amid posters explaining how to vote in the country's presidential election this month, Peruvians wait in chairs lined in rows beside pictures of a faraway paradise: lagoons, ancient cities atop mountains, and llamas. Some 2,400 Peruvians registered to vote at the consulate.

The building's six consulates are part of a relatively sizable diplomatic corps in Greater Boston: The US State Department has registered 91 consular officers and issued 95 consular license plates (which allow diplomats to park for free at meters and designated spots) at 23 official consulates and 32 honorary consulates. Honorary consulates are often US offices designated by countries as a place where their citizens can seek help for anything from consular services to business contacts.

"We have diplomatic representatives from more than 25 percent of the world's countries," says Leonard Kopelman, honorary consul general of Finland and dean of the Consular Corps of Boston, which holds luncheons with local and state officials and this month raised more than $60,000 for the United Nations at its annual "Consul's Ball" at the Fairmont Copley Plaza.

Unlike other cities, such as New York and London, which have fought high-profile battles with diplomats over unpaid tolls and parking fines, Boston has a placid relationship with its foreign envoys, who can also park in commercial spots without fear of being ticketed or towed, city officials say.

"We don't have any problems to speak of," said James M. Mansfield, a spokesman for the Boston Transportation Department, noting diplomats can have their cars towed if they park in handicapped spots.

That doesn't mean there aren't stresses on the city's diplomats, most of whom are paid to deal with a host of crises. (Honorary consuls generally aren't paid.) The easiest part of their job often deals with life and death -- a baby born in the area who needs a birth certificate from their parents' country, widows seeking papers to send a spouse's body home.

At the Dominican consulate, which serves an estimated 70,000 of its citizens throughout New England, Frank Tejeda seems to be in constant motion, often 10 hours a day, six days a week, or a normal Dominican workweek. If he's not meeting officials in Providence or visiting Dominicans in a New Hampshire jail or local hospital, the vice consul is signing powers of attorney, authenticating travel documents, and advising the 70 or so people who walk into the consulate every day, many of whom don't speak more than a few words of English.

"Helping people in a crisis is what we do," says Tejeda, who stamps as many as 100 documents a day and visits about 25 prisoners a month.At the Israeli consulate, on a day when the 18 employees on staff await results of their country's national election, there's a different kind of tension.

For the past eight years, Eddy Caba has experienced it nearly every day. One of the building's janitors, Caba has received special clearance to clean the Israeli consulate, which, unlike for the building's other consulates and offices, he must do during working hours.

Though the staff knows him well, the consulate's security officials still pat him down, search his large, wheeled trash can, and thoroughly check his equipment, even scrutinizing the toilet paper he brings every day. When he's sick, replacements must provide their Social Security number, passport, and have their background checked by police."I understand their concern, but after eight years, it's kind of crazy," Caba says.

A country with only 6 million people, Israel has nine consulates in the United States, its third-largest in Boston, after New York and Los Angeles. Why?

"This is the biggest university in the world, and a major financial capital," says Meir Shlomo, the consul general in Boston. He says he competed with 40 other Israeli diplomats for the posting. "You also have a lot of presidents from Boston. We see this as a good place to look ahead of the curve, and we want to be a part of the intellectual debate."

Serving outside a nation's capital is a different kind of experience for a career diplomat, says Shlomo, who has served in embassies from India to Denmark to El Salvador.

In Boston, outside the intelligentsia, many people don't understand what he does, he says. Out of all his speeches, essays, and meetings over the past four years, he says, his greatest impact may have been made by successfully completing an opening pitch at Fenway.

"When I say consul general, people have no clue what the title means," he says. "If I go to a store and show a tax-exempt card, the people just don't understand what it is."

Jorio Salgado Gama Filho, Brazil's consul general, has a similar problem.

"Americans understand what an ambassador is," he says. "You often have to explain yourself."Brazil's consulate, which serves 250,000 Brazilians in New England, is the city's largest. Nearly 500 people visit the spare offices every day, requiring consul officials to process about 120 passports daily, as well as scores of birth certificates, marriage licenses, visas, and powers of attorney. With lines snaking out the door, the staff of 25 employees had to move last month into a larger space of more than 3,600 square feet.

The chaos of crying babies and hordes of impatient immigrants requires the presence of security guard Joao Sequeira.

When he passes from the building's carpeted halls to Brazil's stuffy offices, Sequeira says, he feels like he's leaving the States and entering Brazil. Lines are long -- they start forming more than two hours before the consulate opens -- and signs are in Portuguese."In a month here, I've seen it all - people desperate for help and couples kissing as they move down the line," Sequeira says. "One guy who was seeking a power of attorney for his mother couldn't remember her name."

Nine floors down in the Mexican consulate, one of the country's 48 in the United States, Rafael Barron has had similar head-scratching moments.

Standing in a room with posters of tequila and a digital sign listing numbers for the 35 or so people who seek new passports every day, the consular official says he once spent about an hour explaining to a US citizen what she needed to do to retire in Mexico.

At which point, Barron says, the woman turned to him and said, "I need to do all this to move to Albuquerque?" He looked at her quizzically, he says, and explained New Mexico is actually a part of the United States.

Down the hall from Mexico's offices, which are decorated with Diego Rivera paintings and pictures of Mayan temples, are the Peruvian and Dutch consulates.

As distinct as those cultures may be, their consulates are staid places, with few adornments beyond their crests and flags. Both keep their staff behind locked doors and glass windows. And both provide a sense of home: The Peruvians offer cans of bubble-gum-tasting Inca Kola to visitors, and all who enter the Dutch domain are greeted by a framed portrait of Queen Beatrix and her late husband, Prince Claus.

The differences between the consulates and cultures often come alive in the photo studio on the building's fifth floor, where every day some 100 residents from each of the countries pay $10.50 for two passport pictures.

Joilton B. Azeredo, the shop's owner and photographer, knows the different photo sizes for each consulate -- the Israelis require the largest pictures, 4 by 4.5 centimeters, and the Dominicans and the Dutch the smallest, 2 by 2 centimeters, he says. The Brazilians, more than anyone else, fuss about their photos, he says, while the Americans, Dutch, and Israelis are all business -- in and out, rarely mindful of how they appear. The Dominicans and Peruvians, he says, often dress nicely for their photos."

The Brazilians are never satisfied," says Azeredo, who is Brazilian. "Their hair has to always be just right; they always want to be more beautiful."

On a recent morning, with Brazilians, Mexicans, and one woman from the Netherlands packed into his tiny office, with toddlers clutching their dolls and elderly men grimacing in front of his Olympus digital camera, Azeredo props up babies in special seats and pleads with a young man to take off his glasses and keep his eyes open.

One long-haired Brazilian woman, who marches in with high heels after having the wrong-sized pictures taken, mutters that she doesn't look pretty enough.

When the rush dies for a few minutes, Azeredo shows the melange of faces on his computer -- white, brown, black, old and young, maybe a half-dozen nationalities.

"This is nice place to work," he says.

E-mail David Abel at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

NO CASH, BUT LOTS OF CACHETFINLAND'S HONORARY CONSUL RELISHES ROLE

By David Abel

Globe Staff

04/23/2006

It doesn't pay to be the local honorary consul general of Finland.

At least, not in cash.

Nor does the lofty title, which amounts to scores of hours a month promoting the Nordic country and helping local Finns with everything from lost passports to working permits, command perks such as exotic travel, diplomatic immunity, or business deals.

For Leonard Kopelman, whose card also identifies him as "dean" of the Consular Corps of Boston, the job doesn't even offer the nostalgia of helping out an ancestral homeland.

Before the Finnish government asked him to become its man in Boston 31 years ago, Kopelman, a native of Newton, had never visited the Montana-sized country of 5 million people, lacked any special education or family ties to the region, and had no idea Finland had been allied with Nazi Germany in World War II.

Why would the busy senior partner at Kopelman & Paige, a downtown law firm with about 60 lawyers, spend so many years in a job he describes as requiring "stamping a lot of stuff and doing a lot of perfunctory work"?