By David Abel | Globe Staff | 3/30/2003

Every cop suffers his own indignities.

Peeling drunken men off sidewalks. Chasing thugs through crowded streets. Even helping an old, incontinent woman change her soiled sheets.

Some cops let it get to them. Too many violent nuts, too many insults, too many petty crimes not worth their time. Eventually they end up behind a desk, pushing papers in some musty precinct.

Not the man dispatchers call Alpha 633.

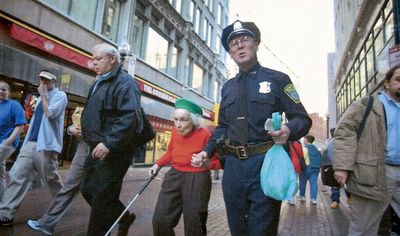

At 61, and one of the city's oldest cops still walking a beat, Officer J.J. O'Malley has become a one-man strike force, a veteran of the roughest streets who has his own definition of preemptive action. In a time of war, with security heightened at home, the short, stocky man in the blue polyester uniform disarms would-be wrongdoers -- his way, without handcuffs.

"I just give them a pat on the back, you know, talk to them a bit, and maybe ask, 'You're not a funny guy, are you?'" says O'Malley, who prefers not to make arrests. "I can be assertive. But I want people to respect me for me, not for my gun and walkie-talkie. There are enough bad guys out there, you don't have to be aggressive with everyone."

Over the past three decades, ever since the city fashioned the area into a pedestrian mall, the patrolman has become known as the mayor of Downtown Crossing. Chatty but vigilant, he keeps a close watch on the tens of thousands of people passing through daily, bonding with everyone from local lawyers to the homeless to tourists.

With Police Commissioner Paul Evans urging 100 officers to leave the force on voluntary retirement to avoid broad layoffs, it's unclear how much longer Alpha 633 will be on the beat.Long a fixture on the evening commute, O'Malley seems to know nearly everyone, as well as their business.

There's the aging prostitute with AIDS who robs her clients. The priest who plays the lottery and takes strolls around midnight. The 22-year-old who recently opened a high-priced hair salon, the Vietnamese guy who loves basketball, and the old man who makes crank calls from a men's room in Filene's.

After roll call one afternoon, he steers his cruiser through the neighborhood and parks it where he always does, just off the corner of Summer and Washington streets.It's a few minutes after 4, the time he's started work for the past 18 years, when he spots a homeless man in a jewelry store.

O'Malley approaches the man, smiles, and quips: "What are you doing, buying a new watch?"

The man laughs nervously, and before bolting, says defensively, "Nope, I'm just gonna go to the shelter early tonight."

Over the course of an average night, he'll respond to calls for burglar alarms and men passed out from guzzling Listerine. He'll also walk a blind 80-year-old woman home, escort the Cape Verdean manager of a fruit stand to her bank, advise the 19-year-old manager of a card store about the ills of smoking, and track down a phonebook to provide directions to lost South Korean tourists.

"He's the people's cop," says Sheila Jordan, a sales clerk at Tello's clothing store who has known O'Malley since he began the beat in 1979. "You ask some officers for help, and they won't do anything. To him, everything's important. He does things he doesn't have to do. That's why people respect him."

The list of his admirers includes the homeless who've been on the streets for years and hustlers whom he and his colleagues have spent months trying to bust.Near dusk he spots Dennis Gaskell, who spent 12 years on the streets of Downtown Crossing. The recovering alcoholic now drives a Cadillac and helps run the shelter where he used to sleep. "He would pour out our liquor and we wouldn't like it," he says. "But he always treated us respectfully, like human beings. Something you don't get from most cops."

Then there's Andre, the 21-year-old guy in flashy clothes, who for hours every day holds court on the corner by Bath & Body Works. Scores of young pals slap his hand, talk about music, and loaf around with him until dark. Through large bifocals, O'Malley watches Andre and says, "I'm sure he's up to no good."

But the man with the black clip-on tie and pointy blue hat takes a different approach from other cops, who've already hauled Andre into the precinct for suspicious behavior. O'Malley jokes with him and his friends, prompting laughs from one large man with a wild Afro when he tells him: "Get a haircut, man."

"I call him 'Officer Friendly,' " says Andre, who insists he's just hanging out in what he calls the "most entertaining part of Boston." "You could say he's like a role model. He's always taking care of the public. You've gotta admire that."

The amiable approach also works, even if O'Malley's not the only reason for the drop in crime.

Since he started commuting from his Lower Mills four-bedroom home, the number of violent crimes in Downtown Crossing has dropped by two-thirds, according to police statistics, and property crimes fell even more. Last year, for example, only 19 vehicles were either stolen or had such attempts made on them, while in 1979 there were 298. In the same time, the number of robberies and attempted robberies dropped from 221 to 46.

With rush hour past, most of the pushcarts gone, and the streets increasingly empty, he laments: "It used to be there was always something going on with all the clubs, pickpockets, and unruly people. Now, I have to check to see if my walkie-talkie's on at night."

Things have changed over the years. He gets half the 16 or so calls he used to receive on an average night, stopping in a bar for a beer is no longer allowed, and his bosses press him to wear a bulletproof vest and carry a gas mask in his cruiser, neither of which he bothers with.

He doesn't lament all the changes, of course.

For one, his pay has improved, from $118 a week when he started on the force 34 years ago to his current weekly salary of $953. Then there are all the friends, like the woman from the Chinese takeout kitchen who flags O'Malley over around dinnertime. Before he walks in, she heaps a generous serving of lo mein, chicken, and fried rice into a takeout box.

The cop can't resist. "They want to give me something," he says, stowing the food in a booth where he stays when it snows or rains. "If I don't take it, I insult her. And the truth is, I don't mind it."

Despite the many changes -- the influx of well-to-do residents and chic restaurants, the new brick walkways and improved lighting, the flourishing of chain stores -- the job's original lure remains: the great mulligatawny that makes Downtown Crossing.

In addition to cornerstones like the 203-year-old Stoddard's cutlery shop, the 164-year-old E.B. Horn jewelry store, and the 128-year-old recently refurbished Locke-Ober restaurant, the neighborhood's stew now includes more college students, living in newly built dorms. New high-rises sprout, like the Ritz-Carlton, as well as the new multiplex movie theater off Tremont Street.

"With all the change, it's nice to know something hasn't -- that Jim O'Malley is still here," says Karl Vulker, who owns the Winter Street Lottery and has known the officer for 15 years. "He's always here for us, always keeping an eye on things."

That will change, perhaps all too soon.

The aging officer, by department rules, will have to turn in his badge in 3 1/2 years -- if he resists the current voluntary retirement pressure. It might be nice to spend more time with his wife, and a grandson recently born to one of his three grown children, but it's a day he isn't anticipating.

Gazing at the golden dome of the State House, with a full moon rising and the late crowd making its way downtown, he inhales, taking in the strangely comforting chaos of the night.

"I don't really consider this work, and sometimes, I think, I can't believe they're paying me for this," he says. "Just look at all these people passing by. These are good people. They've all been places I've never been, and if you open up, you learn things. For me, I think this makes an interesting life."

He waves and jokes with an old friend, offers directions to a stranger, and eventually brings a homeless man to a shelter, persuading officials there to let the man enter, even though he'd been barred for some reason.

Nearly everyone he meets leaves with a smile.

Around midnight, with rats scurrying through the streets and the garbage trucks making the rounds, O'Malley climbs into his cruiser. He takes the long way back to the station, slowing as he passes the darkest alleys.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe